PLAYWRIGHT: You know, it’s really hard to describe how this scene works –

BJJ: because it actually would have been really exciting 150 years ago – having someone caught by a photograph.

PLAYWRIGHT: They were a very novel thing.

Here are a few videos of experts describing and showing cameras from the mid-19th century:

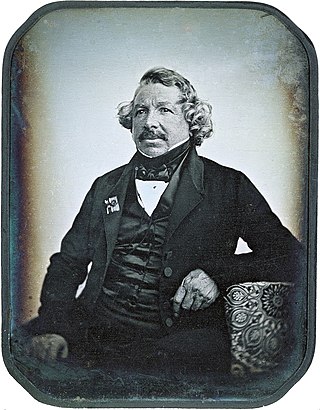

Photography in the 19th century was actually very much rooted in theatre. Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, creator of the most common early photographic process, was a scenic painter and co-owner of the Diorama in Paris from 1822-1839. The Diorama specialized in a form of illusionist entertainment, displaying enormous scenic paintings of exotic places, manipulating them with light, and even placing real objects, animals or people in front of them. As with most scenic artists of the time, Daguerre began his paintings by tracing real scenes using the camera’s predecessor, the camera obscura. It was while trying to find a way of streamlining this process that he developed his “daguerrotype” method of photography (1839-1860).

The camera obscura, one of the predecessors of photographic technology

Daguerre’s Diorama, a popular 19th centure Parisian spectacle involving theatrical paintings, props and lighting effects

Daguerre’s process involved taking a highly polished sheet of silver-plated copper, exposing it to iodine vapors to make it light-sensitive, taking the exposure within the box camera, developing with mercury fumes, and then stabilizing the image with salt water or sodium thiosulphate. The effect was a backwards photograph, reflective like a mirror and somewhat eerie. Close on the heels of the daguerreotype were ambrotypes (1855-1865) which were printed on glass, and tintypes (1855-1900), which were printed on tin and widely introduced less bulky, more portable photos.

A daguerreotype of Daguerre himself (1844), note the tarnish from air exposure

Glass collodion positives (more commonly known as ambrotypes) in a protective case (1860)

Here are two detailed demonstrations of the daguerreotype and tintype photograhic processes:

For the photographer, taking a photograph was half art, half chemistry. For the subject of the portrait, it was generally full-parts uncomfortable. Daguerreotype photography could not capture motion, so the subject had to sit very still for the length of the exposure (which could be as long as 20 seconds). This explains why many early photographs (like Dora’s in OCTOROON) are…awkward.